Death is the only end to the odyssey of the pornographic imagination when it becomes systematic.

-Susan Sontag

Disclosures that lie and soon disappear...

Dead Conversations on Art and Politics:

José Guadalupe Posada interviews John Jota Leaños

We do not torture.

-George W. BushLet the atrocious images haunt us.

-Susan SontagThe conversation from which this article arose takes place between 19th century Mexican artist and illustrator, José Guadalupe Posada (1851-1913) and 21st century New Media artist, John Jota Leaños. The circumstances of this exchange are unusual at best and are located somewhere along the road to Mictlan on the southern border of the ancient Mexican indigenous practice of the Days of the Dead. The cross-hemispheric exchange focuses not only on the death of art, politics, irony in the 21st century, but reflects on the dearth of such exchanges as well as the challenges of performing critical art within the borders of empire.

Section I.

John Jota Leaños: Bienvenidos, Señor Posada. It is with much respect, awe and appreciation that I invite you back to reflect on political art practice in the age of American empire.José Guadalupe Posada: No vengo porque puedo, sino porque puedo vengo. (trans. I return not because you allow me, but I return because I can.) What would you like to talk about?

John Jota Leaños: I would like to fill you in on the historic torture scandal that has arisen out of the American occupation of Iraq. Approximately fifty images of American torture, sexual abuse and humiliation of Iraqi prisoners from the Abu Ghraib prison were released to the public in 2004 and were distributed globally by the media. The images released to the public are only a fraction of the dozens of photographs and hours of video that exist documenting these abuses. The US Senate viewed most of this material behind closed doors, but deemed them “unviewable” and forbade their release to the larger public. There is no telling when and if these images will ever become available, but evidence shows that these “captured” images are only a shadow of the abuses including rape, murder, torture, and humiliation that took place at Abu Ghraib and at other detention centers in Iraq, Afghanistan, Guantanamo, and globally. For the rest of the world, these images of Abu Ghraib abuses have become the face of the US occupation in Iraq. The US corporate media has already forgotten about them having milked the images for all the hype and sensationalism possible, but stopping short of demanding public access to the other images and/or doing thorough documentation and investigation of the situation and the larger implications they have for US imperialism, the prison-industrial complex, ethics in a democracy, etc. As these images are placed in the annals of atrocious war photography, they are also inserted into the photo album of the American Empire, American citizens and artists are faced with a deep and complex matrix of meaning that these images bring to the surface.

José Guadalupe Posada: Seems pretty serious, myfriend! (Laughs) What are you doing about it?

John Jota Leaños: My art practice resides in the struggle of the symbolic arena. I engage in social critique from within the margins of institutional power, challenging Master narratives, employing traditional and contemporary art tactics to create platforms from which to speak, draw connections and formulate meaning by “any media necessary.” The Abu Ghraib torture scandal is the most significant US war abuse scandal since My Lai, Vietnam. As you can imagine, artists and social critics have generated a large body of work with the release of torture photographs. Many artists, including myself, have dedicated time to replicating, reproducing, recontextualizing, and aestheticizing these images. I believe that reproducing these images and saturating the popular consciousness with them (in an advertising sense) may help alleviate or at least challenge the wide spread amnesia and the endemic optimism of many Americans who choose not to take responsibility or confront the horrors of life, war, and death.

Artist working with these images inevitably accept a date with the horrific and shameful. The photos are a glimpse into the acts of exploitation and dehumanization of war in general and the “War on Terror” in particular, and they reveal a pathological culture of arrogance, ignorance and abuse that saturates not only the US military and the upper chains of command (i.e. the Pentagon and the Bush administration), but points directly to the history of white supremacy, murderous imperialism, sexual domination, and, ultimately, the global exploitation of the rendered “evil,” surplus, and exotic ‘other’. These acts and photographs perpetuate this truly American legacy. They are not easy images to deal with.

José Guadalupe Posada: Don’t be such a puritanical gringo, büey! This is what you do ¿a poco no? ... You confront ... the horrors of life with the laughter of death (Laughs). But aren’t you further exploiting, demeaning and dehumanizing the individuals victimized in the photos?

John Jota Leaños: That’s a good question. For artists committed to open democratic discourse, we have to ask ourselves critical ethical questions. The photograph has always been locked in a dangerous dance of representation. When this scandal broke, many people repeated the common mantra, “Photographs don’t lie.” Although these photos do give us a profound glimpse into American prison abuse and torture, they aren’t exactly telling the truth. Photographs are muffled storytellers—they fail to tell a complete story. Many times a photograph will reveal more about the person behind the lens—h/her intention, vision, framing and use of the photograph, etc. These considerations expose the photographer. This is certainly true with the Abu Ghraib photographs. The photographers of these prison 'memories' were trophy hunters documenting their unhappy pleasures and justifying their actions by citing orders to humiliate the hunted game from higher chains of command. The widespread and uniform practice of beatings, hooding, sexual humiliation, murder, and scatological play in Afghanistan, Iraq and Guantanamo Bay discloses the larger dehumanization campaign within factions of the military that has established a culture of systematic sadism. Psychological detachment or “emotional distance” begins in the message system of language—naming the Iraqis ‘hajis,’ ‘it,’ and ‘dogs’. Such an orientation has in part laid the groundwork for American soldiers to treat the Iraqis and anyone deemed ‘enemy’ in such inhumane ways.

The exploitation and dehumanization that you’re talking about happens in the act of torture and in the act photographing. Artists face ethical issues with when entering into the battle of meaning. One of the main ethical and tactical problems in dealing with the Abu Ghraib photos is in the lack of ability to approach the subjectivity or humanity of these victims. How do we lend them subjectivity? How do we respect their humanity in an image in which their humanity has been completely erased? How do we avoid exploiting their pain/death in order to speak to larger historical and political matters? This, of course, is not an impossible task, but a challenging one that is beyond the resources of many artists. Most artists will choose to avoid the maze of subjectivity of the tortured and instead speak to the torture itself (the practices and ideologies the photographs represent) and then move to contextualizing the image in historical, cultural and political contexts. The photos then become a part of a critical struggle of representation against the atrocities of what one might call the Judeo-Christian-Pancapitalist-Military-Idustrial-Entertainment-Prison-University Complex.Since most of us accessed these images on the Internet or on television, we were offered no insight into the exploited and tortured subjects. The mediated message machine (I mean, the corporate media) does not offer access into subjectivity. We don't know the tortured person’s names, age, history, family, etc. We cannot hear their voices, their pleads, their defiance. We only know that these people are most likely Iraqis and that they are being exploited and tortured. We don’t even know if these people are guilty of any crime. (Military specialists estimated that between 70% and 90% of the prisoners held at Abu Ghraib were innocent of any crime and arrested by mistake. In the weeks following photo scandal, the US military released over 800 prisoners from Abu Ghraib. International media—the exception being US corporate media—have since extensively interviewed many of these prisoners. )

José Guadalupe Posada: Pero como artista, aren’t you torturing the prisoner by using these images? (Laughs)

John Jota Leaños: Through my cultural lenses the artist is not torturing the prisoner again by re-presenting h/her image. The image of the person is not the person h/herself, o sea, I believe the image and the person are ontologically separated. However, this does not mean that these images put into different cultural contexts cannot be dehumanizing, demeaning, insulting, and shocking. Is there a decency standard for shocking images? The audience is America, for those who don’t want to look.

José Guadalupe Posada: Excuse me for interrupting, but… do you have a cigarette?

John Jota Leaños: José, you’re dead. You can’t smoke.

José Guadalupe Posada: ¡No importa! Lighten up a bit, will you? Y un tequilita sería perfecto también…. Gracias… Anyway, what were you saying…?

John Jota Leaños: I was about to talk about this net.art piece that I’m working on….

José Guadalupe Posada: I’m sorry…qué es net.art? Is that some sort of new gringo printing process…

John Jota Leaños: Well, sort of, José. Net.art is artwork on the Internet which was actually an initiative by the military-academic alliance back in the classical period of 21st century media.

José Guadalupe Posada: … the Internet?

John Jota Leaños: …ehhhh…as I was saying, in this net.art piece I’m working on, I have tried to demonstrate the lack of representation/subjectivity that the images possess by outlining the subjects of torture and making them semi-transparent, ghost-like. I ask: “How do we understand these acts—the photographs and the torture—as detached voyeurs. The digital voyeur’s vantage point is somewhat determined and definitely limited—the Abu Ghraib photographs are ‘representations’ of the horror of torture and American imperialism. How do we make them real to the passive American? What historical lessons are learned from these photos? What do they tell us about American culture? About American military culture? About American popular culture? About American media culture?

José Guadalupe Posada: ¡Espere! You seem to have more questions than answers, señor… and I thought I was supposed to be asking the questions! My etchings of lynchings, disaster scenes and death scenes spoke to the brutal reality of life. What do these torture photographs speak to?

John Jota Leaños: The transformative power of these photographs is in their potential to move people, to elicit raw, unexcavated emotions. Institutional powers (i.e. the government, corporate media and their sponsors) fear the transformative capacity of images because such emotion shocks (anger, disgust, outrage, empathy!) when connected with rational understanding can potentially result in ideological shifts, political activity and dissent. This is why the Bush administration forbade video or photographs of dead soldier coffins returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. In not showing footage of Iraqi/Afghani innocent victims (of which there is plenty), the corporate media follows the unwritten rules of hegemony.

It is true that the American political right cares deeply about and protects righteously its own image of America. This is why the symbolic arena is so sacred in the U.S. and why the right will fight belligerently to protect its imaginary narrative of America. Protecting a clean image of America is at the forefront of reactionary ideologies in the US. Conservative ideologues, led by the Bush administration, as well as the political mainstream continually frame the Abu Ghraib torture as a game of a few ‘sick’ individuals.

José Guadalupe Posada: Bush! Ese cabrón is worse than that dictator Porfirio Diaz! Is it true that he stole those elections?

John Jota Leaños: Well, the presidency was given to him through a failure of democracy and a directionless opposition.

José Guadalupe Posada: …. So, back to torture photographs, where do you draw the line?

John Jota Leaños: In a video portraying the naked, hooded prisoners dancing in a Western disco, I’ve crossed many ethical borders in order to represent that “brutal reality” that you refer to.

José Guadalupe Posada: What inspired you to do that?John Jota Leaños: Placing the tortured bodies in a disco was ‘inspired’ by the US military practice of blasting loud American music all night long to keep prisoners awake and forcing naked, hooded prisoners to dance. A prison in northern Iraq was nicknamed “The Disco” by American GIs because of this practice. However, this scene is hard to stomach because it seems to perpetuate exploitation and excesses. I still don’t know why this is different from putting the images in a Vietnam War scene, a WWII scene, etc. It is definitely a heavy and perverse scene, but then again, the matter is heavy and perverse.

José Guadalupe Posada: I think gringos need to see more of that! Why don’t los gabachos (trans. Americans) want to see these images? ¿Son demasiado picantes?

John Jota Leaños: The Abu Ghraib images are not much worse than images of simulated violence and death seen everyday in America on television, at the movies and on the Internet. The difference between images of war and atrocity and the ever-present fictionalized representation of death, war and abuse is that war images are for real. The anthropologist, Geoffrey Gorer, talks about how death in our society is treated as obsene and pornographic. Deep discourse on death is avoided and shunned today not unlike pornography was avoided and shunned in Victorian times. In this case, Gorer’s “pornography of death” can be translated to a pornography of torture, a pornography of imperial reality. In spite of the photographic evidence, testimonies and official reports, most representatives from the US government have declared that the “United States does not use torture.” Period. End of discussion. Others have passed it off on a few “bad apples” in the lower echelons of the military. The denial and rationalizations of the US practice of torture and brutal execution legitimizes this practice. To confront these practices, open and active discourse is the first step. It is in the tradition of your printmaking and widely distributed broadsheets, José, that I find inspiration to use new technologies to talk about taboo ideas within the symbolic arena. José? ¿José? Where did you go…?

Editor’s Notes: At this point, the copal failed to burn and the conversation ended just in time.

Section II.

Dead Representation and The Politics of Truth Telling: The Case of Patrick Tillman

In Section II, 19th Century Mexican illustrator José Guadalupe Posada (1851-1913) continues his conversation with 21st Century Xicano Digital Artist John Jota Leaños after another round of tequila. Here Leaños discusses a Días de los Muertos art controversy and the use of film and animation to insert political content.José Guadalupe Posada: Tell me what about your troubles, carnal?

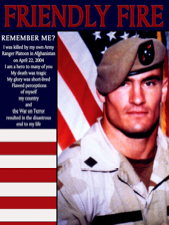

John Jota Leaños: Trouble is easy to come by these days for those interested in practicing democratic critique of imperial dogma. In 2004, I created a Días de los Muertos memorial to Arizona State University graduate, ex-Arizona Cardinal football player, and fallen US Ranger, Patrick Tillman. Pat Tillman was a professional football player who gave up an NFL contract worth millions of dollars to enlist in the US Rangers and fight the war on terror. In April of 2004, Tillman was killed in Afghanistan. According to military press release, Tillman died while fighting Taliban resistance. Tillman was immediately canonized as a great American war hero and deemed imperial martyr by the government-military-media complex. This was at a time when media discourse about the war dead was, for the most part, absent, silent and repressed. A few months later, a quiet Pentagon report released news stating the Tillman was “probably killed by ‘friendly fire’.” The Pentagon, it turns out, lied about Tillman’s death.

The United States military is not known for admitting mistakes in public. The military, however, is known for media-managing heroic war narratives to promote its agendas. The military invented the Jessica Lynch rescue story that was broadcast day and night on all media outlets. After months of being silenced by the military, Jessica Lynch came out and said, “No, none of that happened. I didn’t empty my rifle and kill several Iraqi insurgents. I wasn’t slapped and tortured in the hospital bed.” This was precisely the type of military propaganda that surrounded the Pat Tillman story. Any criticism of Tillman and/or the heroic narrative was met with angry vigilance and/or suppression. At his funeral, which was broadcast nationally by ESPN, one of Pat Tillman’s brothers spoke at the end of the ceremony telling the audience, “Pat Tillman isn't with God. He's fucking dead. He wasn't religious. So thank you for your thoughts, but he's fucking dead.” ESPN quickly edited the speech out of its broadcast.

Tillman’s death by ‘friendly fire’ was confirmed nearly eight months after his death in the winter of 2004 by investigative report from the Washington Post stating that Tillman died unnecessarily after “botched communications, mistaken decisions ... and negligent shooting.” The report critiqued the military for purposely distorting accounts of the events to make it appear as if Tillman died while fighting Afghan forces. One can only speculate why the US military orchestrated this complex cover-up. Tillman’s death did occur on the heels of the Abu Ghraib photograph scandal.

José Guadalupe Posada: So why did you get involved? Didn’t you teach at Arizona State University? What was your commentary on this situation?

John Jota Leaños: I was teaching at Arizona State at the time and I also work in the tradition of Chicana/o art making which has a strong history of performing art in the public sphere that is often critical, sometimes controversial, polemical, anti-imperialist…and definitely political. Part of my job description as a Xicano artist is to comment on society and culture and to critically engage issues that may be taboo, unpopular, and/or culturally sensitive, and to do this in a way in which raises vital questions and complicates conventional discourse especially in times of war.

The Days of the Dead memorial, in the form of 500 24” x 36” posters, was simply titled, “Friendly Fire.” This text is placed over the top of Tillman’s Ranger portrait. On the left, there is text that reads, “Remember me?” speaking to the American culture of 15-minute replaceable heroes. The text continues:

I was killed by my own Army

Ranger Platoon in Afghanistan

on April 22, 2004

I am a hero to many of you

my death was tragic

my glory was short-lived

flawed perceptions

of myself

my country

and

the War on Terror

resulted in the disastrous

end to my lifeI put these posters up in downtown Phoenix and on Arizona State University campus on October 1. A week later, local ABC and CBS Nightly News did stories on this. It was then picked up by CNN and broadcast nationally over the weekend that preceded the presidential debate hosted by Arizona. By bringing Tillman back from the dead in a Días de los Muertos artwork, I was asking the social question, “If Pat Tillman’s image/spirit came back to Arizona speaking to us about the tragedy of his death and the mistakes and errors of war. What would happen?”

José Guadalupe Posada: ¿Y qué pasó?

John Jota Leaños: After the artwork was aired by the media, Internet bloggers took over sending hundreds of emails to my account, to the president of Arizona State University and to the Arizona Board of Regents most demanding that I be fired from my job over the creation of the posters. The State of Arizona launched an investigation into my classroom activities. I received phone calls, hundreds of email messages to date, and was the subject of several rightwing blogs. The messages were filled with repulsive anger, hate, bigotry, racism, homophobia, death threats, and promises of violence. People posted my home address on the Internet and promised to visit.

José Guadalupe Posada: (Laughing) ¿Ah sí? Give me some examples of the mail.

John Jota Leaños: I have about 60 pages of hate mail if you like to see it. But, for example, one blogger instructed others in how to perform their democratic duties:

I have found that a nice email with a little sensitivity works wonders. (Liberal pussies tend to have too many feelings. Kind of like Mr Rodgers...). However, if this does not work he should be hunted down (any volunteers?) and some one should KILL THE FUCK out of him. His boss should be ass-raped like he was in a Federal Ass pounding prison. This should help others decide to think before they open their cum dumpster/cock holsters and spew filth.

Others chimed in:

Big mistake, Puto. Maybe you should get back to mowing my lawn. I mean, that IS what chicano studies teaches, right?

You are a sick fuck. the only thought that your work provokes in my mind is “why isn’t he picking strawberries” i hope you get syphilis.

I hope you are a Mexican fag with AIDS and die soon.

José Guadalupe Posada: (Laughing uncontrollably) Really?… That’s horrible.

John Jota Leaños: This was the general tone of the messages. It is laughably horrible, and its great material for my next project.

José Guadalupe Posada: Ooh. Were you surprised by the reaction?

John Jota Leaños: On the one hand, I am not surprised by the overreaction of the conservative males to this artwork (over 90% of the hate mail I received were from men). It is business as usual on the extreme right to launch hate campaigns, ad hominem attacks, character assassinations and witch hunts to destroy the professions of those who breach certain ideological fronteras. On the other hand, that an artwork which is not slanderous, obscene, pornographic, or racist could incite such vicious reactions is revealing of the times we live in.

José Guadalupe Posada: …and the times we die in… (Laughing) Were you scared?

John Jota Leaños: Being the father of a three year old, I understand that many times the best way to deal with a temper tantrum is to allow it to get out of the child’s system until it passes. The knee jerk reaction to the Tillman memorial was essentially a highly orchestrated temper tantrum by conservative men on computers.

José Guadalupe Posada: And the Tillman family?

John Jota Leaños: Approaching the subject of Pat Tillman and/or murdered soldiers in general is serious business. We should not treat these issues too lightly because we are dealing with a dead son, a dead husband, a dead brother, a dead friend. This is serious business. The Tillman family does not want their son’s image to be part of symbolic war of ideology, but it seems this was out of their hands. After over a year of not speaking to the media, the parents of Pat Tillman spoke very publicly and critically about the military’s lies. They essentially said that they cannot trust the military or this administration who, in their eyes, used the son for their pro-war agenda. It was also reveled that Tillman was against the war in Iraq and an avid reader of Noam Chomsky.

José Guadalupe Posada: ¿Entonces… What…what…why were people so upset?

John Jota Leaños: In dogmatic times, you get dogmatic and authoritarian reactions. Many of the more thoughtful folk were upset because I used first person. “How dare you speak for him?” This is precisely what I was asking, “Who is speaking for Tillman?” If we look at around we’ll find two (unauthorized) books have already written about Pat Tillman. A Hollywood screenplay is in the works and coming to a theater near you may be a film in which an actor will be literally speaking for Tillman. There is merchandizing galore—hats, jerseys, helmets, pins, photos. There was constant nationalistic memorializing juxtaposing his heroic football images with his military portrait and a waving American flag. There was outright profiteering going down. The Arizona Cardinals sold tickets on his name offering free rubber bracelets with Tillman’s name and number on them for the first 10,000 fans to the stadium last season (those same bracelets were being sold for up to $70 apiece on eBay soon after).

My posters were free! But all of the branding, profiting and pro-war usage of Tillman’s image and name are OK as long as they fit into a certain ideological framework that portrays Pat Tillman as a perfect, fixed and untouchable hero. But, as soon as someone comes out and says, “Wait a second. He was killed by ‘friendly fire.’ His death is tragic and revealing of a misguided war on terror”. If this happens, then all hell breaks out.

José Guadalupe Posada: ¡Alli está el detalle! The pinche hypocrisy and self-righteousness of the dictatorship!

John Jota Leaños: Well, José, this is not exactly a “dictatorship,” but artists from Critical Art Ensemble who are being tried as we speak by the federal government for doing artwork under the Patriot Act, think (y con razón) that this government is in a proto-fascist state. This is supposedly a “democracy,” so it’s vital that we put democratic precepts into practice. We must test the limits of free speech. We must encourage dissent and active participation of artists and citizens.

José Guadalupe Posada: Sí, sí. But why do you think men, in particular, were so angry at this artwork?

John Jota Leaños: The questions of gender, specifically expressions of American masculinity, are fascinating. There are the obvious connections between expressions of masculinity, the military and football. But given the types of responses that I received—with the homophobic/femalephobic responses, (the “pansy” and “fag” name calling) coupled with the racist overtones—I believe that this poster—and it is just another poster—disrupts white masculinity as it relates to American imperial identity. Tillman or rather the image of Tillman may be an expression of Imperial White Masculinity. I’m not saying that Pat Tillman, the man, was a white supremacist or that he embodied these ideals, but that his image has been ideologically constructed in this lineage. There is a strong white-male war hero lineage in the American imaginary streaming from Gary Cooper, John Wayne, and Sylvester Stallone to Ronald Reagan and Arnold Schawrzenegger (we see the line begins to blur between Hollywood images and American Politics). I’m sure George W. Bush would like to write his name into this lineage too as well.

The Tillman memorial could be seen as a tactical disruption—disrupting fixed imperial discourse with well-placed messaging and inciting, for better or for worse, open democratic discourse. It might also be called tactical revealing—revealing the underbelly of power structures.

José Guadalupe Posada: (Laughing) Are you serious?

John Jota Leaños: No, not really. I realize, though, that this type of critique is not tolerated in mainstream America today as is evident in widespread attempts to police dissent.

José Guadalupe Posada: Police? You didn’t mention anything about police…

John Jota Leaños: José, this country has a long history of policing and silencing dissent during times of war. From Sedition Act of 1798, Lincoln’s suspending of Habeus Corpus, to the internment of the Japanese and McCarthyism of the Cold War, from the active political harassment and disruptions of the CointelPro Operations to the present concentration camps of Guantanamo Bay…and everything that fell in between. The recent Patriot Act seems to be a regressive upgrade of surveillance and oppressive operations that is technologically driven and firmly in the lineage of this rich, rich American history of suspending free speech during times of war.

José Guadalupe Posada: So the “Man” is watching over you? (Giggles)

John Jota Leaños: We find ourselves in a deeply woven surveillance society that is embedded in the cultural mythology of the West. We have the omniscient, ever-present Eye of God spying on us. The eyes of mommy and daddy watch over us. There is the myth of Big Brother. Even Santa Claus knows when we’re sleeping, he knows when we’re awake, he knows if we’ve been bad or good, so be good for goodness sake!

José Guadalupe Posada: Don’t tell me you believe in that Papa Noel mierda (trans Santa Claus bs)?

John Jota Leaños: No, my point is that in this society we’re either being watched, we think we’re being watched and thus watching ourselves (the pathos of self-surveillance) or we’re doing the watching (straddling the thin line between voyeurism and surveillance).

There is extensive government-corporate surveillance and a strong mythology that accompanies it. But what I’m talking about, in this case, is ideological surveillance by the citizens. I’m talking about this regressive political correctness that has emerged since 9/11/01 and the neo-McCarthyism facilitated and fueled by digital culture that advances extreme opinions. I’m talking power of bloggers and extremists in digital culture, about the disembodied, detached blogger mania, blogger ire spurred by rightwing reaction to unflattering facts about the military and/or the idea of their nation.

José Guadalupe Posada: You got another cigarette?… Thanks. Perhaps an uninviting offering was made to the dead in this work….

John Jota Leaños: …You think?

José Guadalupe Posada: Just joking, jefe!… ¡Dios mio! Where’s your sense of satire?

John Jota Leaños: You may be right, José. However, in the context of a divided country in the midst of two disastrous wars and in a highly contested presidential election, I thought that serenity, confession, honesty and regret were appropriate tactics.

It’s been said that in a time of “infinite war” irony and satire are dead. The logic is this: At a time when warfields are expanding and empire is being assaulted (in the case of 9/11), we can no longer afford the luxury of ironically commenting on the situation from a distance. Although I identify with the spirit of this theory, I don’t agree with its conclusion. These are severe political times, but more pressing than other moments or places in history? If we turn away from satire, humor and irony, we lose perspective of our larger responsibility to humanity and culture, digo yo, and we risk becoming dogmatic revolutionaries that lead to book burnings…

José Guadalupe Posada: Book burnings? Is that what you’re talking about?

John Jota Leaños: No! You’re so distracted, José….

José Guadalupe Posada: OK, OK, OK… Much of your work deals with dead people. Are you into necrophilia? Do you see dead people?

John Jota Leaños: Not precisely. I work to carry on your practice of a Days of the Dead tradition that re-imagines the dead, that is, our ancestors, as active participants in our everyday decisions, political realities and social constructions. I have turned to animation and filmmaking to speak to a larger audience around these issues.

José Guadalupe Posada: Ay, moving pictures! I love that stuff!

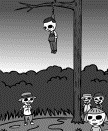

John Jota Leaños: Yes, may people love to look at cartoons to suspend their sense of reality. However, I am practicing documentary animation which literally draws from reality within a fictitious time and space. I find this rupture quite effective. My first animaton, Los ABCs ¡Qué Vivan los Muertos!, is a cute cartoon about those dead of war who have been forgotten, neglected and/or, literally, left hanging. It is drawn from historical and real life situations, such as the Women of Juarez or the lynching of blacks, Indians, Mexicans and Chinese in America. The animation has a catchy song sung by dead Mariachis that draws the viewer into familiar and comfortable spaces of laughter and song while shockingly reminding them about the murderous and white supremacist foundation and maintenance of America, its doctrines, its Master Narrative, its ideals. It’s a work about remembering your ABCs of empire, a sort of primer for understanding the “other” side of American history in the age of ADD, fast cuts and historical amnesia.

Documentary Animation: This animation cell from Los ABCs was drawn from the “trophy photo” on the right of the lynching of Rubin Stacy in Fort Lauderdale, Florida in 1935.I have also completed an animation called, DNN: Dead News Network, which take the expression, “Don’t fear the media, become the media!” quite literally by creating an animated dead news series that not only highlights stories that are ignored and forgotten by the corporate news networks, but also offers satirical solutions to endless problems such as Global Warming and the US-Mexico border as well as giving political projections for the upcoming (s)election.

We are at a historical moment in which alternative, do-it-yourself media, video and filmmaking is at its height and whose conscious practice builds independent, self-reliant citizens who can begin to decolonize their learning and knowledge, thus opening a plethora of possibilities, platforms and ways of living.

José Guadalupe Posada: Ay, those are good skills to exercise. But why bring up the past, hombre? Why not let sleeping dogs die, let diegones be diegones.

John Jota Leaños: Because we still live in a democracy, José. A widely accepted strategy of controlling discourse is in silencing voices of dissent that don’t take on the mainstream, militarist, imperial points of view and being silent during times of war including the American cultural custom of being silent in the face of death. (I mean real death, not simulated Hollywood video-game death). There is a silence and absence of images and discourse of the war dead, no images of coffins returning from Iraq, no coverage of the thousands of innocent Iraqis slaughtered by American forces,

Silence es igual a la muerte. Silencio equals Death. The AIDS activists of the 1980s warned us of the dangers of being silent during crisis. Silence is also a space from which oppressed voices speak and are heard. We should we return to this question of silence, of imperial silence, that deafening and deadly silence that helps America pretend that it is the beacon of freedom and democracy.

So if the solution to this imperial silence is to embrace it, to demonstrate the absence, talk about the unpopular, to articulate that which is not said, then we will not be surprised and hopefully be prepared for the ad hominem attacks, character assassinations, threats on our lives and wellbeing, and witch hunts to destroy us professionally. These are tactics of the intolerant and boisterous right and these are the challenges of performing critical art in a time of declared infinite war. ¡Seguimos adelante!

José Guadalupe Posada: Let the Dead of War Speak! ¡Qué Vivan los Muertos!

Mictlan is the lowest level of the underworld where the dead reside in Aztec mythology. The dead travel far north to Mictlan guided by a psychopomp. During the Days of the Dead celebration, the dead often return to the living finding their way with the smell of zempazuchil (marigolds) and by the light of the vela (candle).

As this conversation takes place, a US District federal judge has ordered the US government to release 74 photogrpahs and three video tapes from Abu Ghraib prison to the public. See Judge Orders Release of More Abu Ghraib Photos at CNN.com, Thursday, September 29, 2005.

For globalized practice of torture, see ‘extraordinary rendition’ practices by the US and other governments in “Outsourcing Torture: The secret history of America’s “extraordinary rendition” program” by Jane Mayer in The New Yorker, Issue 02/14/2005.

For translations and transcripts of some of these interviews with prisoners tortured at Abu Ghraib, see Torture and Truth: America, Abu Ghraib, and the War on Terror by Mark Danner New York Review Books, 2004

For report, see Army Finds Tillman Probably Killed by Friendly Fire: Former pro football player killed in Afghanistan, Monday, May 31, 2004 at CNN.com